Credit: Cell Reports Physical Science (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.xcrp.2024.102151

In

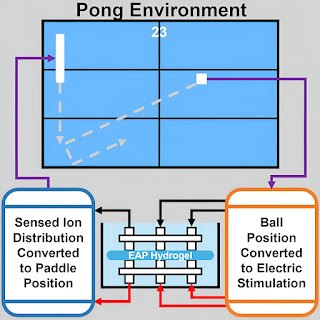

a study published22 August

in Cell Reports Physical Science, a

team led by Dr. Yoshikatsu Hayashi demonstrated that a simple hydrogel—a type

of soft, flexible material—can learn to play the simple 1970s computer game

"Pong." The hydrogel, interfaced with a computer simulation of the

classic game via a custom-built multi-electrode array, showed improved

performance over time.

Dr. Hayashi, a biomedical engineer at

the University of Reading's School of Biological Sciences, said, "Our

research shows that even very simple materials can exhibit complex, adaptive

behaviors typically associated with living systems or sophisticated AI.

"This opens up exciting

possibilities for developing new types of 'smart' materials that can learn and

adapt to their environment."

The emergent learning behavior is

thought to arise from movement of charged particles within the hydrogel in

response to electrical stimulation, creating a form of 'memory' within the material

itself.

"Ionic hydrogels can achieve the

same kind of memory mechanics as more complex neural networks," says first author and robotics engineer,

Vincent Strong of the University of Reading. "We showed that hydrogels are

not only able to play Pong, they can actually get better at it over time."

The researchers were inspired by a

previous study that showed that brain cells in a dish can learn to play Pong if they are

electrically stimulated in a way that gives them feedback on their performance.

"Our paper addresses the question

of whether simple artificial systems can compute closed loops similar to the

feedback loops that allow our brains to control our bodies," said Dr.

Hayashi, a corresponding author on the study.

"The basic principle in both

neurons and hydrogels is that ion migration and distributions can work as a

memory function which can correlate with sensory-motor loops in the Pong world.

In neurons, ions run within the cells. In the gel, they run outside."

Because most existing AI algorithms are derived from neural networks, the researchers say that hydrogels represent a different kind of "intelligence" that could be used to develop new, simpler algorithms. In the future, the researchers plan to further probe the hydrogel's "memory" by examining the mechanisms behind its memory and by testing its ability to perform other tasks.

Gel plays Pong. Credit: Cell Reports

Physical Science/Strong et al.

Beating gel mimics heart tissue

In a recent related study, published in the Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences, Dr. Hayashi's team, along with Reading colleagues Dr.

Zuowei Wang and Dr. Nandini Vasudevan, demonstrated how a different hydrogel

material can be taught to beat in rhythm with an external pacemaker. This is

the first time this has been achieved using a material other than living cells.

The researchers demonstrated how

a hydrogel material oscillates chemically and mechanically,

much like the way heart muscle cells contract in unison. They provide

theoretical interpretation of these dynamic behaviors.

The researchers found that by

applying cyclic compressions to the gel, they could entrain its chemical

oscillations to sync with the mechanical rhythm. The gel retained a memory of

this entrained beating even after the mechanical pacemaker was stopped.

"This is a significant step

towards developing a model of cardiac muscle that might one day be used to

study the interplay of mechanical and chemical signals in the human

heart," Dr. Hayashi said. "It opens up exciting possibilities for replacing

some animal experiments in cardiac research with these

chemically-powered gel models."

Lead author of the study, Dr. Tunde

Geher-Herczegh, said the findings could provide new ways to investigate cardiac arrhythmia, a condition in which the heart beats too fast, too

slow or irregularly, which affects more than 2 million people in the UK.

She said, "An irregular heart

beat can be managed with drugs or an electrical pacemaker, but the complexity

of biological heart cells makes it difficult to study the underlying mechanical

systems, independently from the chemical and electrical systems in the heart.

"Our findings could lead to

new discoveries and potential treatments for arrythmia, and will contribute to

our understanding of how artificial materials could be used in place of animals

and biological tissues, for research and treatments in the future."

Implications and future directions

These studies, bridging concepts

from neuroscience, physics, materials science, and cardiac research, suggest

that the fundamental principles underlying learning and adaptation in living

systems might be more universal than previously thought.

The research team believes their

findings could have far-reaching implications for fields ranging from soft

robotics and prosthetics to environmental sensing and adaptive materials.

Future work will focus on developing more complex behaviors and exploring potential real-world applications, including the development of alternative lab models for advancing cardiac research and reducing the use of animals in medical studies.

Source: Pong

prodigy: Hydrogel material shows unexpected learning abilities (phys.org)

No comments:

Post a Comment