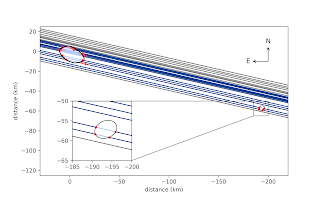

On the night of July 7, 2022, the Lowell Discovery Telescope near Flagstaff, Arizona captured this sequence in which the asteroid Didymos, located near the center of the screen, moves across the night sky. The sequence is sped up by about 900 times. Scientists used this and other observations from the July campaign to confirm Dimorphos’ orbit and anticipated location at the time of DART’s impact. Credits: Lowell Observatory/N. Moskovitz

Using some of the

world’s most powerful telescopes, the DART investigation team last month

completed a six-night observation campaign to confirm earlier calculations of

the orbit of Dimorphos—DART’s asteroid target—around its larger parent asteroid,

Didymos, confirming where the asteroid is expected to be located at the time of

impact. DART, which is the world’s first attempt to change the speed and path

of an asteroid’s motion in space, tests a method of asteroid deflection that

could prove useful if such a need arises in the future for planetary

defense.

“The measurements the team made in early 2021 were

critical for making sure that DART arrived at the right place and the right

time for its kinetic impact into Dimorphos,” said Andy Rivkin, the DART

investigation team co-lead at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics

Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. “Confirming those measurements with new

observations shows us that we don’t need any course changes and we’re already

right on target.”

However, understanding the dynamics of

Dimorphos’ orbit is important for reasons beyond ensuring DART’s impact. If

DART succeeds in altering Dimorphos’ path, the moonlet will move closer toward

Didymos, shortening the time it takes to orbit it. Measuring that change is

straightforward, but scientists need to confirm that nothing other than the

impact is affecting the orbit. This includes subtle forces such as

radiation recoil from the asteroid’s Sun-warmed surface, which can gently push

on the asteroid and cause its orbit to change.

“The before-and-after nature of this

experiment requires exquisite knowledge of the asteroid system before we do

anything to it,” said Nick Moskovitz, an astronomer with Lowell Observatory in

Flagstaff, Arizona, and co-lead of the July observation campaign.

“We don’t want to, at the last minute, say, ‘Oh, here’s something we

hadn’t thought about or phenomena we hadn’t considered.’ We want to be sure

that any change we see is entirely due to what DART did.”

In late September to early October, around

the time of DART’s impact, Didymos and Dimorphos will make their closest

approach to Earth in recent years at approximately 6.7 million miles (10.8

million kilometers) away. Since March 2021 the Didymos system had been out of

range of most ground-based telescopes because of its distance from Earth, but

early this July the DART Investigation Team employed powerful telescopes in

Arizona and Chile — the Lowell Discovery Telescope at Lowell

Observatory, the Magellan Telescope at Las Campanas Observatory and the

Southern Astrophysical Research (SOAR) Telescope — to observe the

asteroid system and look for changes in its brightness. These changes, called

“mutual events,” occur when one of the asteroids passes in front of the other

because of Dimorphos’ orbit, blocking some of the light they

emit.

“It was a tricky time of year to get these

observations,” said Moskovitz. In the Northern Hemisphere, the nights are

short, and it is monsoon season in Arizona. In the Southern Hemisphere, the threat

of winter storms loomed. In fact, just after the observation campaign, a

snowstorm hit Chile, prompting evacuations from the mountain where SOAR is

located. The telescope was then shut down for close to ten days. “We asked for

six half-nights of observation with some expectation that about half of those

would be lost to weather, but we only lost one night. We got really lucky.”

In all, the team was able to extract from

the data the timing of 11 new mutual events. Studying those changes in

brightness enabled scientists to determine precisely how long it takes

Dimorphos to orbit the larger asteroid and thereby predict where Dimorphos will

be located at specific moments in time, including when DART makes impact. The

results were consistent with previous calculations.

“We really have high confidence now that

the asteroid system is well understood and we are set up to understand what

happens after impact,” Moskovitz said.

Not only did this observation campaign

enable the team to confirm Dimorphos’ orbital period and expected location at

time of impact, but it also allowed team members to refine the

process they will use to determine whether DART successfully changed

Dimorphos’s orbit post-impact, and by how much.

In October, the team will again use

ground-based telescopes around the world to look for mutual events and

calculate Dimorphos’ new orbit, expecting that the time it takes the smaller

asteroid to orbit Didymos will have shifted by several minutes. These

observations will also help constrain theories that scientists around the world

have put forward about Dimorphos’ orbit dynamics and the rotation of both

asteroids.

Johns Hopkins APL manages the DART mission for NASA's Planetary Defense Coordination Office as a project of the agency’s Planetary Missions Program Office. DART is the world's first planetary defense test mission, intentionally executing a kinetic impact into Dimorphos to slightly change its motion in space. While neither asteroid poses a threat to Earth, the DART mission will demonstrate that a spacecraft can autonomously navigate to a kinetic impact on a relatively small target asteroid and that this is a viable technique to deflect an asteroid on a collision course with Earth if one is ever discovered. DART will reach its target on Sept. 26, 2022.

For more information about the DART

mission, visit: https://www.nasa.gov/dartmission

Source: DART

Team Confirms Orbit of Targeted Asteroid | NASA

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)